The Cost of Maize Rush in the Drylands of Tamil Nadu

India’s maize production is surging, driven by rising demand from the ethanol, poultry, and feed industries. Tamil Nadu doubled its Kharif maize output in 2024-25. But pest attacks, poor seed quality, and rising input costs worry farmers. Maize’s dominance is also squeezing out traditional crops like pulses, raising concerns about sustainability, farmer income stability, and food security.

Maize is called the queen of cereals and is an important crop globally. Leading producers of maize like the USA, China, Brazil and Argentina are pushing for higher production of maize for livestock feed (61%), industrial (22%) and food purposes (17%). India is also being pushed to catch up by consistently increasing the production of maize. For instance, it increased production from 225.67 lakh MT in 2015-16 to 376.65 lakh MT in 2023-24.

Tamil Nadu was the fourth-largest producer of maize in India in 2023-24 producing 7.5% of the total production. The area of production has increased almost two times from 2.3 lakh hectares in 2010-11 to 4.3 lakh hectares in 2022-23 and production has increased almost three times from 10.3 lakh MT to 29.9 lakh MT.

This trend is here to stay. According to the First Advance Estimate, maize production in Kharif season 2024-25 in Tamil Nadu is 17.54 lakh MT, almost double compared to the 9.74 lakh MT produced in Kharif 2023-24.

A sudden rise in demand for maize in India

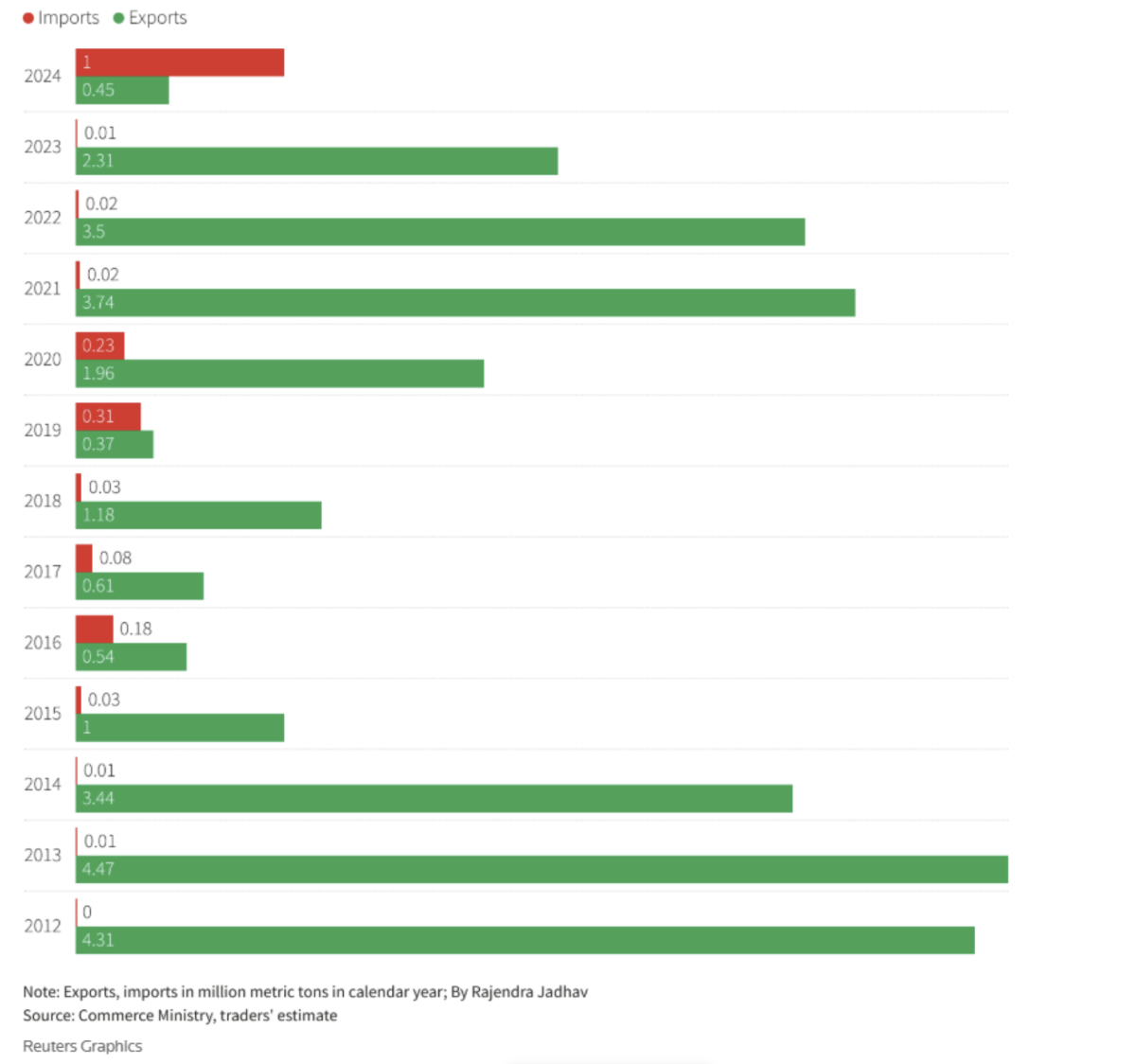

The increase in maize cultivation over the year can be attributed to increasing demand for maize with the poultry industry contributing majorly. Despite the demand, India was a net exporter of maize until recently. The export of maize touched an all-time high of 37.27 lakh MT in 2021-22.

Things took a turn suddenly in 2024-25 as India became a net importer of maize. The maize imports to India as on December 2024 was more than 10 times the imports of the last four years put together. The government had allowed import of maize under tariff rate quota (TRQ) at 15% import duty through state government agencies.

The sudden shift can be attributed to an increased demand of maize for ethanol production.

“The jump in import demand comes after the Indian government hiked the procurement price of ethanol made from maize in January, 2024 to drive a shift away from sugarcane-based ethanol for blending in petrol. Traditionally, the poultry and starch industries absorbed most of India’s corn production of around 360 lakh MT. In 2023-24, ethanol distilleries started using maize, and their demand grew this year (2024-25) after the government abruptly curbed the use of sugarcane for fuel following a drought. That led to a shortfall of 50 lakh MT,” an official with the All-India Poultry Breeders Association told the media.

The percentage of India’s ethanol made from food grains like maize and rice increased from 37.4% (2022-23) to 51% for November 2023-October 2024. This is the first time that the contribution of grains to India’s ethanol production has surpassed 50%. In fiscal 2024-25, till June 9, India produced 357.12 crore litres of ethanol, of which, 175.74 crore litres came from sugar and 181.38 crore litres from grains, of which maize alone contributed 110.82 crore litres (31% of the ethanol produced). The ethanol production from maize further increased to 231.49 crore litres by September 30, 2024 (approximately 60 lakh MT would have been used to produce that quantity).

The seeds of this transition were sown in 2018, when the Modi government initiated the Ethanol Blended Petrol Programme. As per the “Roadmap for Ethanol Blending in India 2020-25”, the estimated requirement for 20% ethanol blending in ethanol supply year (ESY) 2025-26 is approximately 1,016 crore litres and another 334 crore litres of ethanol will be required for other uses.

Producing this vast quantity of ethanol would require around 60 lakh MT of sugar and 165 lakh MT of food grains per annum in 2025. Moreover, since the share of grain-based ethanol production has increased from 2021 when the report was made, we can expect an even higher demand for maize for ethanol production.

Impact of maize rush on farmers

While the demand for maize is increasing and the price of maize constantly rising, it is not a completely rosy picture for the farmers. Various incidents of maize crop failure in large tracts of land due to poor quality of seeds and pest infestation have been reported across Tamil Nadu (and other parts of the country).

As per media reports, poor quality of maize seeds has affected farmers in Perambalur in August, 2024, and Tiruppur farmers in February, 2022, while over 1,000 acres of maize crops in Dindigul were affected in June, 2024. Similarly, farmers cultivating maize in 3,500 hectares in Madurai and other nearby districts like Ramanathapuram, Theni, Sivaganga and Talavadi Hill, Erode were affected due to the American fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) pest attack in December of 2023, as well as 2024.

American fall armyworm infestations led to increase in usage of chemicals and thus leading to an increase in maize cultivation cost for farmers. As per a study, between 2017 (pre-invasion) and 2020 (post-invasion), Karnataka maize farmers spent an additional USD 49.32 per hectare (average of four years) on pesticides for pest control. The maize yields during 2020 were largely at par with those in 2017, but the cost of plant protection per hectare, per season increased 10 times in 2020.

Concerns from the ground

Kannan, a farmer from Ogalur, Perambalur district has shifted from maize cultivation to kodo millet cultivation with the support of Nammalvar Organic Millet Farmers’ Producer Organisation.

“Last year (2023) my maize crop got lost due to American fall armyworm. It might be due to less rain. I only got one bag (100 kg) whereas usually I get 15-20 bags (1500 – 2000 kg) in my 2 acres farm,” he says.

Sumathi, a women farmer from Kiliyur, Perambalur district, cultivates maize in three acres and millets or pulses in one acre of farmland.

“I spent Rs 50,000 for maize cultivation last year (2023) but the crop failed due to no rains. However, kodo millet planted in the 1 acre withstood that and gave a decent harvest. It compensated for the loss from the 3 acres of maize cultivation and I also supported my family with that income” she says.

Sumathi notes, “Maize cultivation is like a lottery ticket as it has a higher cost of cultivation and requires water. If the yields are good, you will get good income, but if not, you will incur heavy losses.”

Ganesan, field staff at Nammalvar Organic Millet Farmers’ Producer Organisation, says, “Recently, cattle died because they were fed with maize stover in which kurunai (chemical input to protect from fall armyworm) was used.”

A local trader in Anthur, Perambalur district, says, “Maize is mainly bought for chicken feed, cow feed, ethanol production and export.” He procures around 10,000 – 15,000 quintals from 200-300 farmers in the area. “Maize became famous in the 2000s, earlier, millets and pulses were the main crop. Today, even farmers who have irrigation facilities for growing Paddy or sugarcane are shifting to maize. The current market price for maize is Rs 2500 – Rs 3000/quintal.”

A threat to food security

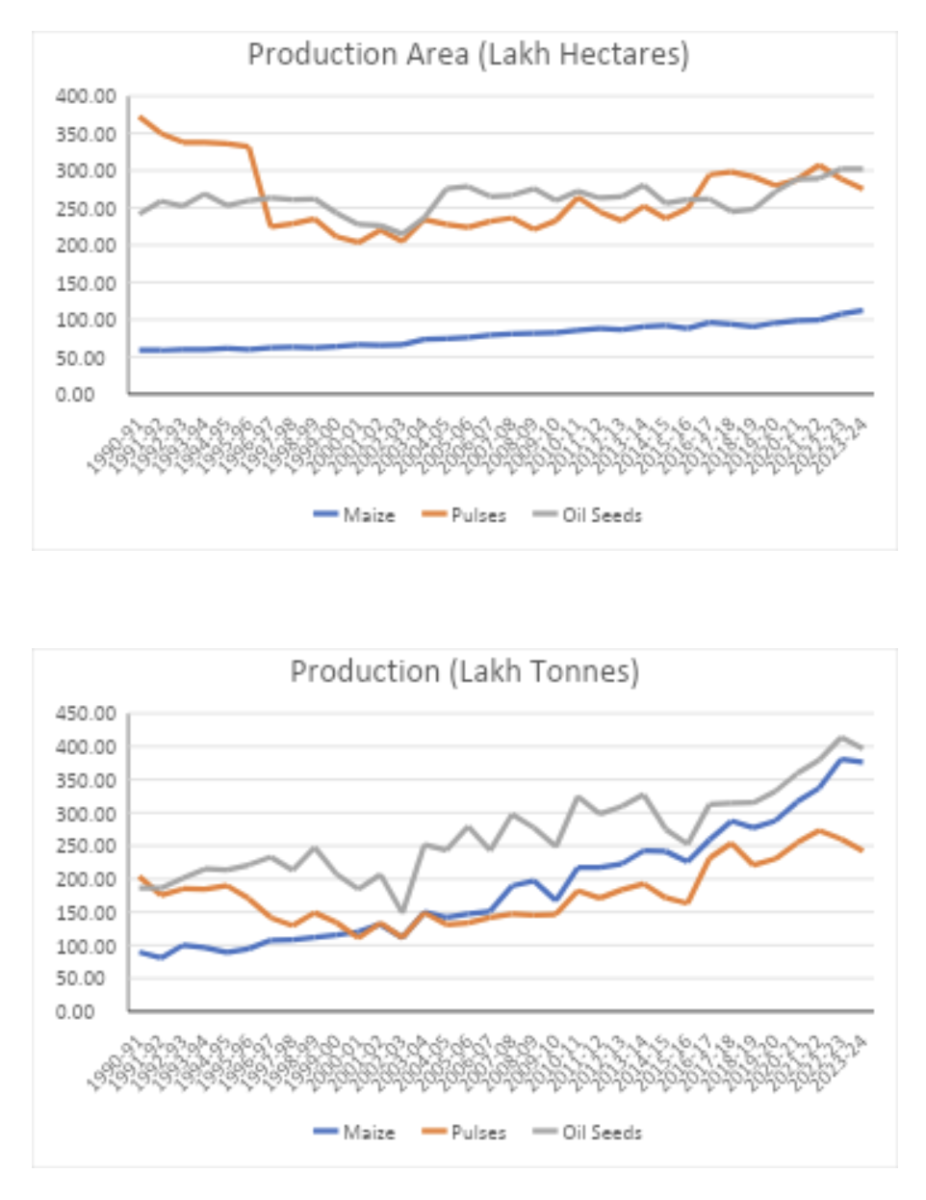

Almost four-fifth of maize grown in India is rainfed and cultivated in dryland areas where millets, pulses and oilseeds are the other main crops. The total production area of pulses in India has decreased from 372.55 lakh hectares in 1990-91 to 274.94 lakh hectares in 2023-24 (decreased 26.2%) going as low as 203.48 lakh hectares in 2000-01. The total production area of oil seeds in India has increased by 25.03% while maize production area increased by 90.4% in the same period.

The total production of pulse has increased by meagre 19.02% from 1990-91 to 2022-23 while the production of maize has increased by 320.27% in the same period.

India imports almost 15% of the country’s consumption of pulses. The imports skyrocketed 84% to 46.5 lakh MT of pulses in the fiscal year 2023-24 (up from 25.3 MT in 2022-23), the highest since 2018-19. Similarly, India’s import of edible oils – palm, soybean and sunflower – rose 17% on year to a record 164.7 MT valued at Rs 1.38 lakh crores in the 2022-23 oil year (November-October). India imports about 56% of its total annual edible oil consumption.

The scenario is not going to improve in the near future. As per the paper by NABARD and ICRIER, India will continue importing large quantities of pulses and oilseeds by 2030-31. It is evident that further increase in maize cultivation will reduce the production of millets, pulses and oilseeds, thus increasing the dependency on import of pulses and oilseeds and threatening the food security of India.

Is this paving the road for GMO?

A study by NIFTEM, Thanjavur in November 2024 detected illegal genetically modified maize in processed and unprocessed maize produced in India. While the incident may not have been directly linked to increasing demand for maize in India and import of maize from other countries, it is a possibility that cannot be completely eliminated.

With the emerging trends favouring an increased production of maize, it is imperative for India to be cautious as well. The government should analyse this critically to avoid any catastrophic damages.

Will this increase the farmers’ income? Are there any problems and risks in large scale cultivation of maize? What is the impact of this on India’s food security? What is its impact on people’s health and the environment? Many questions need to be answered.

To Read more about Maize News continue reading Agriinsite.com

Source : The Wire