Farmers’ protests, MSP, and wages: MSPs for 23 crops and minimum wages can create food inflation and fiscal problems

Farmers have demanded legalization of MSP at C2+50% profit for 23 crops, raising MSPs by 25%, and 200 days of MNREGA employment at ₹700/day. The latter could cost over ₹10.4 trillion, straining the budget. MSP hikes may shift cropping patterns and inflate food prices by 20-30%. The government is urged to lift export controls, improve futures markets, and end consumer biases for sustainable agricultural reform and fair farmer compensation.

Protesting farmers have put forward 12 demands. Of these, at least two have large economic implications. The first is the legalisation and increase of the MSP at C2+50% profit for 23 crops. For these, the government sets the MSP. The second is the assurance of at least 200 days of employment under MNREGA with a daily wage rate of Rs 700.

The comprehensive cost (C2) includes, besides paid out costs and imputed wage for family labour (A2+FL), imputed rent on owned land and imputed interest on owned capital. If the government accepts this formula, then MSP levels for 23 crops will go up, on average, by 25% over the 2023-24 MSPs. Within this basket of 23 commodities, the MSP increase will vary across crops. While safflower MSP will go up by 40%, sugarcane’s FRP will go up only by 3%, wheat by 9%, and mustard by 8%, as their existing MSPs are already well above the C2+50% margin. MSPs would increase for sesamum (37%), sunflower (32%), soybean (31%), groundnut (26%), paddy (31%), jowar (33%), maize (29%), ragi (30%), tur (28%), moong (27%), urad (35%), gram (25%), and lentil (14%). Commercial crops’ MSP will also go up—cotton (24%), copra (31%), and jute (21%). These MSP hikes would change the relative prices of these crops and could prompt shifts in cropping patterns. Wheat and sugarcane are likely to lose area, while paddy surpluses may go up significantly. This may force higher MSP hikes in wheat and sugarcane than indicated by C2+50% formula.

Price hikes in commodities like soybean and maize, which are basic feed material for poultry, fishery and dairy, will push the prices of such products, leading to high food inflation. Additionally, the allure of stable MSPs of 23 crops may attract many producers of horticulture, which can create shortages of fruits and vegetables, leading to higher inflation for them. Thus, overall, it seems that food inflation may go up by 20 to 30%.

Making MSPs legal will be more problematic for farmers. Take the case of rice, whose MSP will go up by 31% under the new MSP formula. All exports of rice, about 22 mt, would become unviable, adding to domestic supplies. When MSP of paddy goes up by 31% and sugarcane by only 3%, paddy will start substituting even sugarcane and many other kharif crops, creating a glut in the domestic market. And when supplies may far exceed demand, traders will not touch the excess supplies for fear of being harassed and fined. How much can the government buy and then distribute via PDS, and at what cost? It is hard to estimate how much fiscal cost it can inflict on the government if deficiencies are paid for—it will depend upon the difference between market price and MSP, and the price these commodities are unloaded in the market.

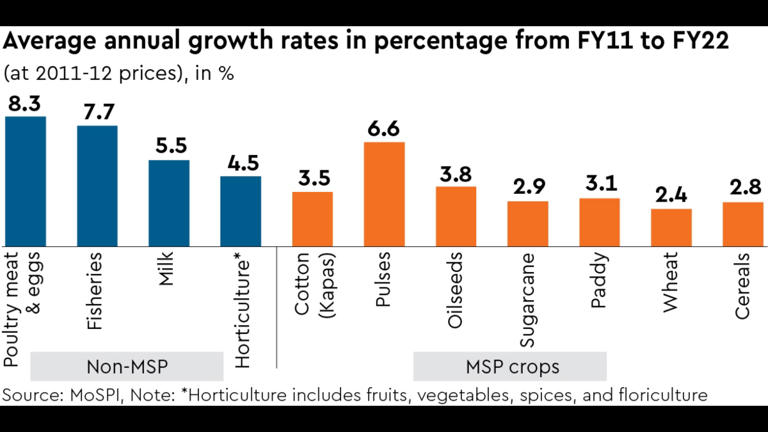

It is worth reiterating that the value of the MSP segment constitutes less than 28% of agricultural output. More than 72% of agricultural produce faces market prices and is performing much better than rice, wheat and sugarcane. The average annual growth rates during FY11-FY22 have been 9.1% for poultry meat and 6.3% for eggs, while combined poultry (meat and eggs) has grown by 8.3% pa. Fisheries have grown at 7.7%, milk at 5.5%, and horticulture at 4.5%. These constitute the non-MSP segment of agriculture.

Even within the MSP crops, pulses grew at 6.6%, and oilseeds at 3.8%. Here, government intervention is meagre. The slowest growth is for sugarcane (2.9%), paddy (3.1%), and wheat (2.4%), where the government intervenes heavily. Clearly, per the trends, agriculture is moving to where demand surges quickly.

The farmers’ other demand—200 minimum days of employment under MNREGA at a wage rate of Rs 700 per day—poses a significant fiscal cost to the government. Currently, the budgeted amount for MNREGA stands at Rs 86,000 crore (RE 23-24), based on an average of 48.7 days of employment per household, at a weighted average daily wage of Rs 236.6 in 2023-24. If we consider a minimum daily wage of Rs 700 for 200 days, the estimated budgeted amount would be more than Rs 10.4 trillion! This will be huge fiscal burden in a central budget that hovers around Rs 47 trillion. If one adds in this the demand for pensions and loan waivers, it will simply blow the budget out the window.

However, our sympathies are with the farmers, who deserve a better deal for prices of their produce. The first policy change that is needed to give them a fair deal is to remove export controls and stocking limits on traders. The unloading of rice and wheat below economic cost by the FCI should stop as well.

Second, the government must strengthen and free up futures markets, options, and the warehouse receipt system, and encourage FPOs to be part of organised value chains on digital commerce. It should intervene only when there is a sudden price crash. For that, an augmented stabilisation fund could be used as a last resort, and not the first instrument.

What all this means is eliminating urban consumer bias, who always want lower prices, often at the cost of farmers. This mindset must change. Hopefully, one can talk rationally about it after the general election.