Pitambara and Bishwa Bhaskar Choudhary

NUTRITIONAL well-being has become a significant concern in recent times. According to reports, more than half of the global population suffers from malnutrition, indicating a lack of essential micronutrients such as vitamins and minerals. Empirical research indicates that malnutrition could lead to potential economic losses of up to $125 billion worldwide by 2030, with India alone accounting for around $46 billion. Various forms of malnutrition result in an annual loss of 4 per cent of India’s GDP. Among the nutrients, protein, lysine, tryptophan, iron, zinc, vitamin A and vitamin C are essential for human nutrition, and their deficiency leads to various health disorders. Nonetheless, increased agricultural production, economic opportunities and the National Food Security Act have contributed to food security over the years; the severity of malnutrition necessitates more agricultural interventions.

The production of micronutrient-rich non-staples such as vegetables, pulses, fruits and animal products has also increased, but their affordability is less in comparison to staple cereals for people with low purchasing power. Biofortification — the process by which the nutritional quality of a crop is enhanced through genetic manipulation that includes both breeding and transgenic approaches — could be a viable agricultural intervention to enrich micronutrient density in commonly consumed cereals such as rice, wheat and maize. The biofortified varieties are 1.5 to 3 times more nutritious than the traditional ones. Rice variety CR Dhan 315 has excess zinc; wheat variety HD 3298 is enriched with protein and iron, while DBW 303 and DDW 48 are rich in protein and iron. Maize hybrid varieties 1, 2 and 3 are enriched with lysine and tryptophan and finger millet varieties CFMV 1 and 2 are rich in calcium, iron and zinc.

Developing cultivars

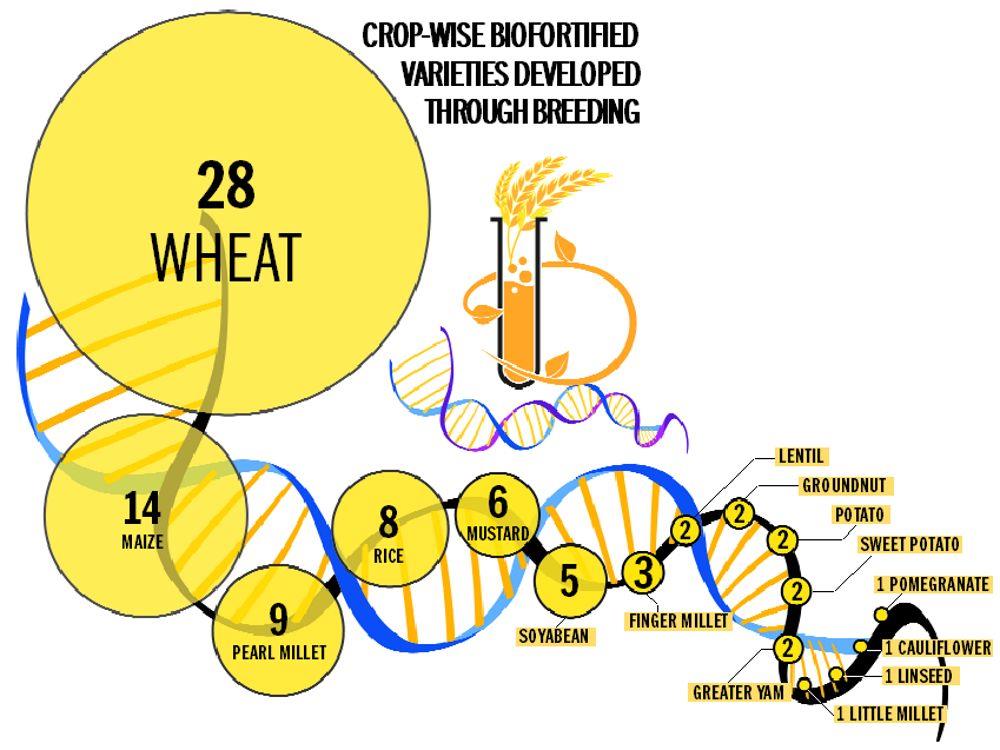

As per a recent report of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), the council has developed 87 biofortified cultivars in 16 crops that can be integrated into the food chain to enable better health of human and animal populations. Staple grains emerged as a critical food source during the Covid-19 pandemic in India due to their cost-effectiveness for low-income segments, widespread availability in contrast to perishable goods, and distribution through the Public Distribution System (PDS). Hence, even marginal enhancements in the nutritional profile of staple grains could significantly contribute to combating micronutrient deficiencies across the country.

The ICAR has started several special programmes on the development and popularisation of biofortified crops. More than four million hectares is estimated to be under cultivation of biofortified crops in India. Reportedly, by 2019-20, the council, through its vast network of research institutes across the country, had developed 21 varieties of biofortified staples, including wheat, rice, maize, millets, mustard and groundnut. These biofortified crops have 1.5 to 3 times higher levels of protein, vitamins, minerals and amino acids compared to the traditional varieties. The Government of India has implemented programmes to address micronutrient malnutrition, such as the National Nutrition