The free market comes to Pakistan’s wheat crop

The death knell for Pakistan’s massive wheat subsidy programme was sounded by the International Monetary Fund, which announced in early September that provincial governments would be barred from setting crop prices as part of its $7 billion bailout package, board approval for which Pakistan secured only a few weeks ago. It is possibly one of the reasons why the Punjab Government has abolished the provincial food department, replacing it with a new autonomous body.

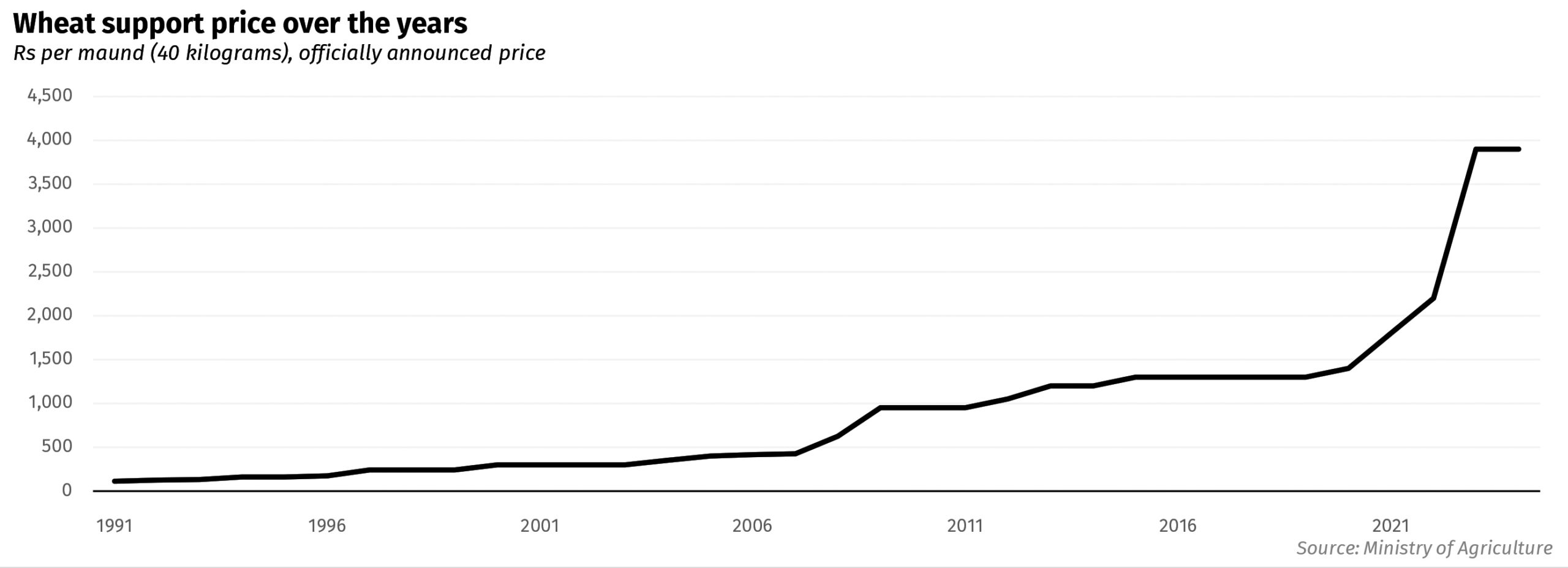

Two years. That is how long the Punjab Government has to phase out the wheat support price it issues every year. It is a subsidy addiction that has afflicted the entire country since at least 1968, but Punjab has year in and year out been the biggest offender.

The death knell for Pakistan’s massive wheat subsidy programme was sounded by the International Monetary Fund, which announced in early September that provincial governments would be barred from setting crop prices as part of its $7 billion bailout package, board approval for which Pakistan secured only a few weeks ago. It is possibly one of the reasons why the Punjab Government has abolished the provincial food department, replacing it with a new autonomous body.

The wheat support price is a bigger problem than one might realise. The concept behind wheat procurement is that the government buys wheat from farmers at a set rate which is higher than what they would get on the market so they continue to grow what is a strategically important crop. The problem is, provincial governments borrow heavily from commercial banks to fund these operations.

In 2023, for example, the wheat procurement target was 40 lakh tonnes and the government had set a price of Rs3,900 per maund (a unit of measuring weight equal to 40 kilograms), or around Rs97.5 per kilogram. To buy this much wheat from farmers at this rate, the government would need around Rs394 billion. Now, the government sells the wheat they acquire to flour mills at this rate so they do recover this money. However, the government relies on borrowing this sum from commercial banks. At an interest rate of 23% in 2023, the government would be paying around Rs90 billion in monthly instalments of 10 months through selling wheat to flour mills. The government also always procures more wheat than it needs and consistently has leftover grain from previous years in storage.

On top of this, the government also needs to spend tens of billions of rupees on handling, transportation and storage costs incurred by the PASSCO on a federal level. The government regularly fails to live up to its commitment with commercial banks, and over time, this has led to circular debt. In 2020, this had risen to Rs757 billion.

Why then do we insist on having these wheat support prices every year? The government will tell you that their aim is to give confidence and provide security to poorer farmers, as well as get cheap flour to the markets. They are lying. All indicators and an impressive body of academic literature on the topic tells us leaving crop prices up to market forces is what is best for farmers.

Farmers would make more money without a wheat support price, even though they have become heavily dependent on it. But breaking that habit might be a good thing. The removal of the wheat support price will allow farmers to possibly look towards other crops as well, and if the government moves on allowing GMO crops such as maize and corn, it can prove to be a gamechanger.

But before we get into that, it is important to understand the nature of the problem and how deep that runs. And that requires answering a basic question: How does the current wheat procurement system work?

The centrality of wheat in Pakistan’s economy

What is today modern Pakistan is the result of the British Empire’s appetite for wheat. The British constructed railways in what is now Pakistan in 1855, in no small part due to a desire to connect the wheat-growing parts of Punjab and Upper Sindh to the port in Karachi.

In 1886, the British were able to start building the Punjab Canal Colonies, which were a series of large, previously sparsely inhabited areas in Punjab, that were brought under cultivation through the use of canals that diverted water from the province’s five rivers. Those canals allowed for previously landless and poor farmers to settle in newly cultivable regions, and the railways helped them sell their surplus crop to the rest of the British Empire.

The British would begin building similar infrastructure for Sindh and Balochistan in 1923, with the construction of the Sukkur Barrage.

With the completion of these large rail and irrigation projects, the volume of commerce between Punjab and Sindh, in particular, exploded. On the eve of the First World War in 1914, Karachi had gone from being a small town on the coast of the Arabian Sea to becoming the largest grain port in the British Empire, and Punjab had become its principal bread basket. Karachi’s significance to the world was as the entrepot that provided access to Punjab’s wheat.

So central is wheat to Pakistan’s conception of itself that it is one of the four crops in the State Emblem (the other three being cotton, tea, and jute; the latter two were the principal crops of East Pakistan, but we will not spend too much time on that awkward remnant of history).

Yet despite this centrality of wheat, at independence, Pakistan’s population had grown so rapidly that it became a net importer of wheat. Indeed, a major initial bone of contention in the Cold War was the race between the United States and the Soviet Union to supply Pakistan with wheat. Between 1949 and 1952, nearly all of Pakistan’s wheat imports came from the Soviet Union. The US considered it a major foreign policy victory to get Pakistan to accept imports from the United States from 1953 onwards.

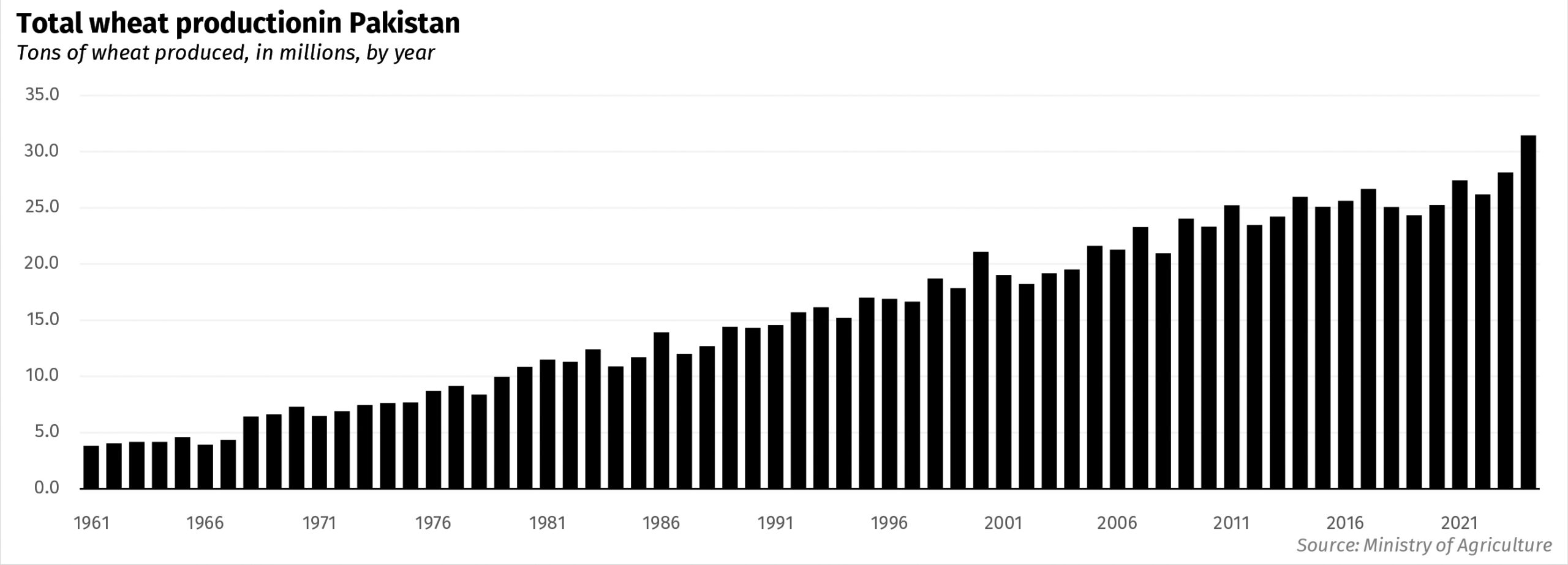

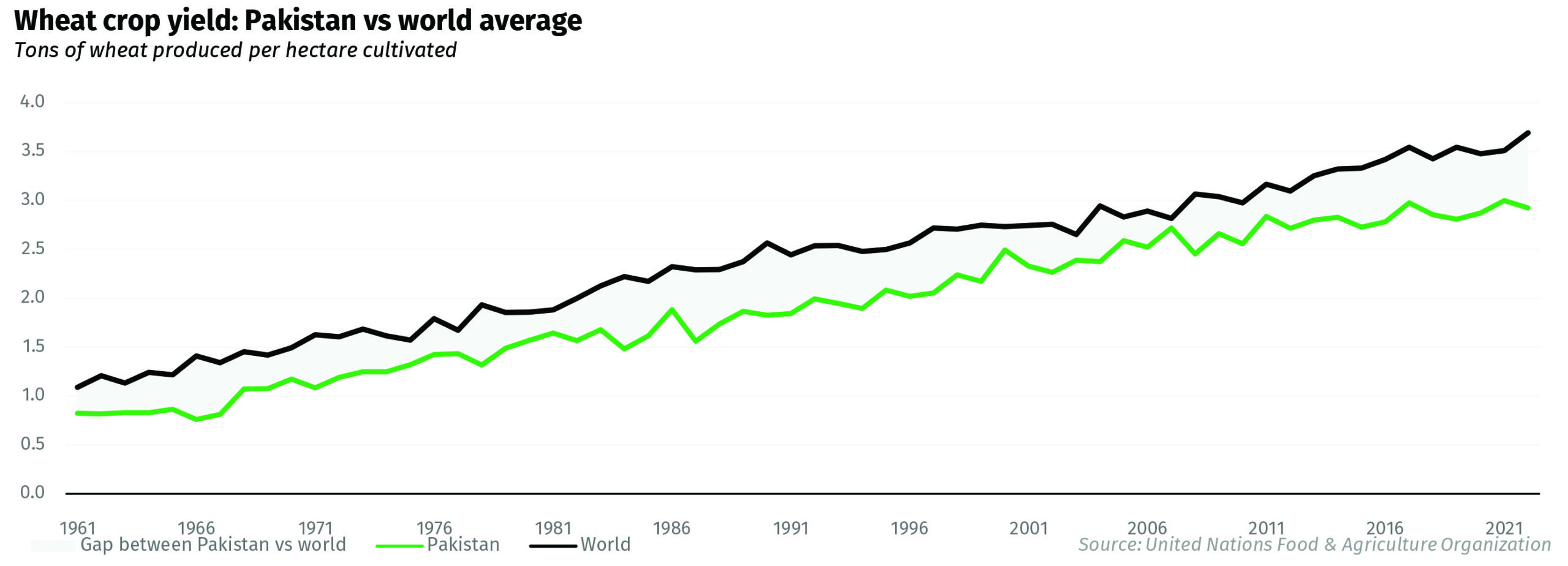

Within Pakistan, however, the reliance on imported wheat was seen as a national embarrassment, and one of the handful of the successful policies initiated by the pre-Ayub governments was to embark on a program to help Pakistani farmers improve the quantity of wheat produced in the country. By the latter half of the Ayub era, the government succeeded.

As a result of this, in 1968, Pakistan had a massive increase in wheat yield. This was the second year running this had happened, and farmers were struggling because the markets had not cleared all of their crop. This was a little embarrassing for the government, which had incentivised growing more wheat since at least the early 1960s to account for food security. Wheat makes up nearly a third of the caloric intake by an average Pakistani, and Pakistan’s per capita consumption of wheat is 124 kilograms annually, which is the highest in the world.

Ad powered by advergic.com

The government decided they would buy the excess wheat from the farmers and store it for a rainy day. This would give the farmers a buyer, their crop would not go to waste, and they could reliably plant it again next year. This was a slippery slope. Gradually, the government became the principal buyer and the private sector’s role shrank. To keep flour prices low for poor households, it established an extensive network of ration-shops, which provided subsidised wheat flour to low-income households. The ration system was abolished in 1987 due to partial targeting, inefficiencies and corruption.

The ration system was replaced with a subsidy on wheat issued to flour mills by the government from its procured stocks. Thus, a targeted subsidy was replaced by a general subsidy that ultimately became far more expensive than the one it replaced. The twin requirements of clearing stocks during harvest season and providing subsidised wheat to flour mills later in the year led the government to procure progressively larger volumes of wheat each year.

The next big change came in 2008, when the 18th amendment was passed and the provinces were made responsible for setting procurement prices and getting the wheat. This is where the current system in Punjab comes into play. How does it work?

Bureaucratic hell

In Punjab, the government’s wheat procurement system is a bureaucratic labyrinth designed, in theory, to support small farmers by purchasing their wheat at premium prices. But in practice, it is a spectacle of inefficiency, political patronage, and frustration, where the people it is supposed to help are often left out in the cold—sometimes literally, since the wheat they grow has a better shot at being stored under plastic sheets than fetching a fair price.

Remember, of all the wheat that Pakistan produces around 60% of it is consumed by the growers either directly or for seed purposes. Of the remaining 40%, the government consumes around the lion’s share leaving only around 10% that sells directly to flower mills which give much lower prices than the government gives.

Every year since 2008, the Punjab Food Department (PFD) purchases about 18.6% of the province’s wheat production. However, the system is not tied to actual needs, like the production levels or what flour mills demand. No, the PFD often buys just enough to ensure its granaries are stocked to the brim, with significant leftover stock gathering dust—and storage costs—year after year. This inefficient hoarding occasionally results in millions of tons of carryover wheat, as was the case in 2009 when the PFD procured 5.78 million tons, resulting in 2.93 million tons of carryover stock the following year. The price tag on storing all that wheat? Huge. And it is the kind of inefficiency that makes a small farmer’s heart sink.

For the farmers, especially the smallholders for whom this system is supposedly built, the journey begins with an infuriating step: getting their names on the patwari list. This list, managed by local land record officials, is the golden ticket to even start the procurement process. But if you are a tenant farmer—or worse, a politically unconnected one—good luck. Tenants are often left off the list, thanks to landowners who do not want them included, and the unholy trinity of bureaucracy, politics, and poor record-keeping means even legitimate farmers frequently find their names missing. Sure, you could technically appeal, but that means preparing tenancy agreements (many of which are verbal) and making endless rounds of government offices. For most, it is easier to sell their wheat at a loss to middlemen than try to fight the system.

Once you have made it past that hurdle, you are handed another one: bardana, the jute or polypropylene bags that you must use to supply your wheat. The bags are rationed out by PFD, and like so many things in the wheat procurement system, who gets them depends less on their crop yields and more on their connections. Well-connected farmers can secure them swiftly, while others wait in agonisingly slow-moving queues. For the average farmer, this means navigating a carefully cultivated system of political favours to ensure a steady supply of bags, all while paying a deposit at a bank (Rs134 per jute bag or Rs38 for polypropylene) before the bags can even be issued. The entire back-and-forth between procurement centres and banks can stretch out for days or weeks.

Once the bardana is secured, it is a race against time. Farmers who have their bags filled must transport them to their designated procurement centres. This requires renting a trolley—an expense most small farmers can ill-afford—since only the largest farms have the means to transport all of their stock at once. An average trolley can carry 100 bags, but many small farmers do not produce enough wheat to justify multiple trips. And even those who manage to get their wheat to the centre face a gamble: not all centres have a weighbridge, so a random 10% sample is weighed, meaning some unlucky farmers find themselves shortchanged during the process.

The worst part? Farmers have to bear all transportation costs and labour expenses. Casual labour at these centres is hired to help unload the bags, stitch them, and weigh them, and while PFD offers a Rs. 9 per bag reimbursement for labour, they don’t cover the costs of filling or stitching the bags or transporting them to the centres in the first place. Farmers are left holding the bill for this, on top of the 5-6% losses that occur in open storage—losses that PFD is happy to shove off onto them.

And let’s not forget the waiting. PFD likes to spread out its procurement operations from mid-April to the end of May, with each farmer being assigned a preferred delivery date. On paper, it should take five to six hours to complete the transaction, but in reality, it can take far longer. If you show up early or late, or if the centre’s having a busy day, you could be stuck for an entire day without compensation for your time. And should the centre’s storage hit its unofficial target early, it might just stop procuring, leaving the less-connected farmers out in the cold.

Even when they do manage to sell their wheat, the payment process is another grind. For smaller consignments, farmers might get cash on the same day. But if they’ve sold more than 50 bags, they receive a slip, which means yet another trip—this time to a designated bank. By the time all is said and done, a farmer may have visited the procurement centre three times and the bank twice, burning between seven and ten days just to get paid. And for what? A system that claims to support small farmers but makes them jump through hoops, wasting valuable time they could spend on the next planting season. The losses pile up—whether in the form of the 1 kg per maund PFD shortchanges during delivery or in the form of delayed payments that stop farmers from paying off debts or ploughing their fields in time for the next crop.

For small farmers strapped for time and cash, the option to sell at lower market prices to intermediaries becomes increasingly appealing. Farmers often need quick cash to settle debts, rent tractors, or pay for inputs like fertiliser and seeds for the next planting season. As one farmer put it, “I had only 15-20 days after the wheat harvest during which I had to plough my land to clear it of weeds and to get it levelled. I do not have a tractor, so I rent it. But I can either rent one before everyone else needs them or after they’re done. I can’t possibly make the rounds to banks and food centres.”

In bumper years, like 2017 and 2018, the government’s incompetence shines even brighter. Unable or unwilling to buy all the wheat, the PFD conveniently adopts a “go-slow” strategy, rationing bardana to only a select group of politically favoured farmers. The rest are left in a queue that moves so slowly, they are forced to sell their wheat to private traders at lower prices. In those years, market prices hovered between Rs1,100 and Rs1,250 per maund, while the government price was Rs1,300. But with the government sitting on massive carry-forward stocks and reluctant to buy, only the well-connected made it through the system.

In the end, what should be a safety net for small farmers becomes an entangling trap. A web of bureaucratic red tape, political patronage, and inefficiency forces them into a system where they are chronically shortchanged. They look up to the PFD for aid, but all they receive are delays, lost wages, and mounting frustrations. At every turn, they face a system designed to exclude the very people it claims to serve, leaving them with little choice but to sell at a loss or spend days navigating a bureaucratic maze. If anything, the wheat procurement system feels less like public intervention and more like a slow-motion betrayal of the people who feed the nation.

So who benefits?

Data for wheat procurement is not updated, with the latest collected information available up to 2020. That is why in our explanation we focused so much on the 2018-19 season, which marked the 10 year mark since the Punjab government began this operation on its own.

What becomes clear is that farmers are not benefitting from this. Data on wheat production by farm size in Punjab shows that 13.3% of farms do not produce wheat at all. Of the 86.7% farms that produce wheat (comprising 63.7% of the total area of private farms), 90.5% percent are smaller than 12.5 acres. This means 78.5% of total farms producing wheat are small farms. These farms are only 40.5% percent of the total farm area and 63.6% of the area of farms reporting wheat. Very small farms of less than one acre do not sell wheat because they do not have a marketable surplus.

Data on wheat production by farm size are not available, but assuming that they produce at the national average of 800 kg wheat per acre and consume wheat flour at 140 KG per person, with an average household size of 6.3, they produce less than their own consumption even when they allocate the entire area to wheat production. Together, non-wheat-producing farms and very small farms are 22.2% of all farms in Punjab.

Then who is benefitting from this? One answer might be commercial banks. On paper, the Punjab Food Department’s (PFD) subsidy structure is meant to stabilise the market, protect farmers, and deliver cheap wheat flour to consumers. In reality, it is more of a balancing act on a tightrope of debt, where the government throws money around with one hand while borrowing furiously with the other. And as you might expect, it is the farmers—and the taxpayers—who ultimately bear the cost.

The subsidy system is straightforward in its premise: PFD buys wheat from farmers at a price that is often higher than the open market and then turns around to sell it to flour mills at a below-market rate. The idea is to keep flour prices stable, prevent market crashes that would hurt farmers, and provide cheaper wheat flour to consumers. On one front, it works—PFD has largely succeeded in smoothing out seasonal price fluctuations, reducing volatility, and keeping flour prices from skyrocketing (a win in a country where food inflation can lead to serious political unrest). But that is about where the good news ends.

Take 2017-18 as an example. That year, PFD’s wheat operations racked up a staggering cost of Rs.34.4 billion, with the bulk of this cost (over 70%) attributed to something that has little to do with actually feeding people: bank mark-up. The PFD borrows money every year to purchase wheat, and while it manages to sell that wheat to flour mills, the government never quite gets around to repaying the entire amount. Instead, it kicks the can down the road, paying off only part of its debts and leaving the remainder to accumulate. This results in PFD not only having to pay interest on its current loans but also on its mounting, unpaid liabilities. For the past five years, this interest alone has averaged Rs19.6 billion per year—just the cost of borrowing money to keep the wheels of wheat procurement turning.

This enormous financial burden has not stopped the government from charging ahead with its operations. PFD continues to borrow from a consortium of banks every year, and the amount it borrows always exceeds what it manages to repay. On paper, this looks like a government subsidy helping farmers, but in reality, the system is bleeding money. Since 2008, except for a couple of rare years, PFD has borrowed more than it has repaid, with no real plan to clear the outstanding debt.

The Punjab government, meanwhile, allocates a modest Rs10 billion each year for wheat operations, knowing full well that this amount is just a drop in the ocean of what is actually needed. The unspoken agreement seems to be that the government will pay off only the interest on the loans (or at least part of it), while the debt continues to balloon in the background.

This cycle of debt does not just hurt the government—it adds to the frustrations of farmers who are already navigating a flawed procurement system. While the government likes to boast about the high prices it offers to farmers, those prices come with significant caveats. In years when the open market price is higher than the official price, PFD imposes bans on inter-provincial wheat movement to force farmers to sell to them. So, the small farmer—already boxed in by bureaucracy and patronage games—finds himself trapped once again, this time forced to accept a lower price because the government needs to meet its procurement targets.

What about the end consumer?

And this is what it comes down to. How expensive is atta for you and me sitting in our homes in urban centres. The government would like to argue that due to their procurement wheat becomes cheaper. It is an argument that has been very succinctly refuted by Ahsan Rana, a professor at LUMS, in a paper he wrote a few years ago:

“Will the price of wheat flour rise by the amount of subsidy if PFD stops wheat operations? Certainly not. Instead, flour prices may decrease due to two reasons. First, in the absence of public intervention, the wheat price will fall at the harvest time and traders will stock up at these low market prices. Second, the private sector’s wastage and storage/transportation costs will be lower than PFD incidentals. Thus, mills’ net cost will be lower than it is in the current interventionist regime.

What will be the net effect if PFD procures wheat but without having to pay interest on the piled-up outstanding debt? Data shows that borrowing in 2017 accounted for only 36.6% of the total PFD debt. If PFD had to pay mark-up only on its borrowing for current operations, its incidentals would be correspondingly less. Adjusting the mark-up gives us a figure of Rs. 205 per 40 kg for PFD incidentals, where there is no outstanding debt. If PFD procures wheat at the official price and if it pays mark-up only on new borrowing, its cost price of wheat at the time of issuance to flour mills will be Rs(1,300 + 205.19 =) 1,505 per 40 kg. If PFD provides no subsidy at the issuance of wheat, cost of flour will increase by Rs205 per 40 kg; if it provides subsidy at the current level (viz. Rs. 379 per 40 kg), cost of flour will decrease by Rs(205.19 – 379 =) 173.81 per 40 kg, ceteris paribus. In other words, consumers are paying Rs173.81 extra per 40 kg for Punjab government’s failure to retire its outstanding debt.”

It shows in the receipts

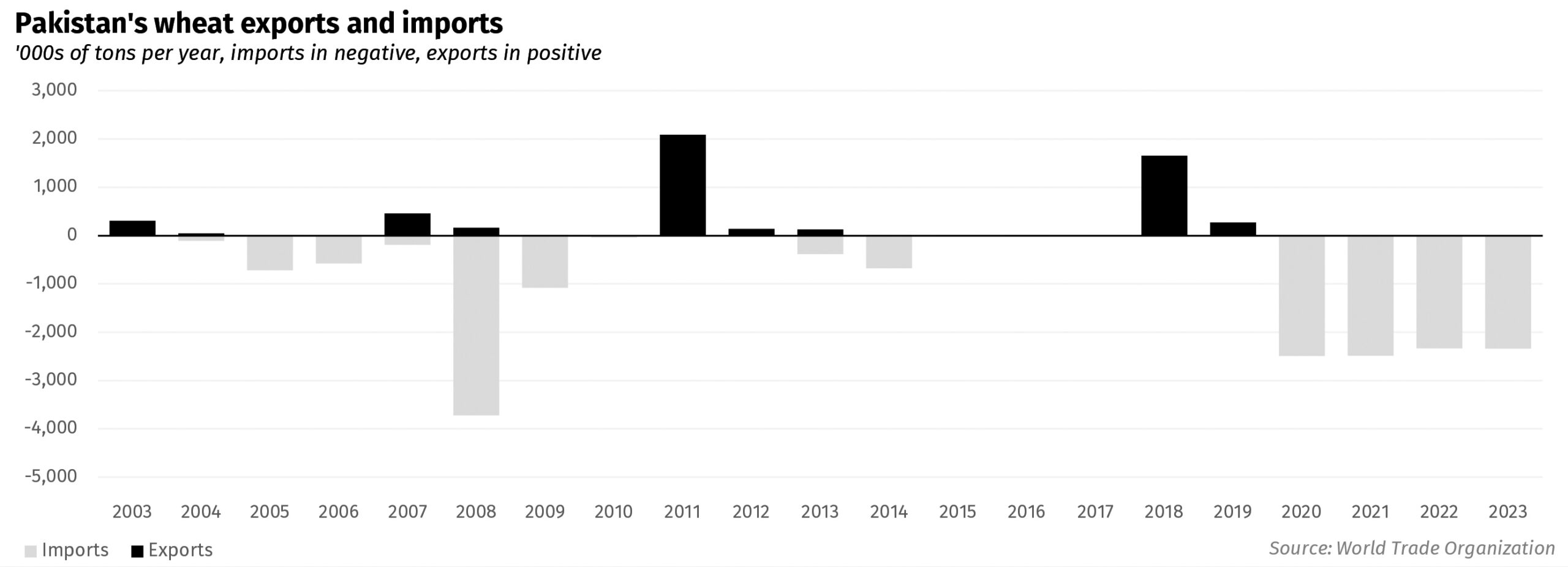

All of this points towards why wheat procurement has been such a consistent problem in Punjab. Perhaps nothing points towards this better than the billion dollar wheat import scandal of 2023-24 that the Punjab and federal governments are still suffering from.

It is the latest chapter in Pakistan’s broken wheat procurement system—an emblem of everything wrong with how the country handles its most essential crop. In this case, the ruling Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) found itself embroiled in internal tensions over how to address a scandal that is as much about political manoeuvring as it is about financial mismanagement. Former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif pushed for strict accountability against the caretaker government that oversaw the import of 1.2 million tonnes of surplus wheat. However, his brother, current Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif, hesitated, reluctant to implicate members of his own coalition, including those with ties to the establishment.

The roots of the scandal go back to a bureaucratic blunder that allowed wheat imports far beyond what was necessary to compensate for the 2022 floods, allegedly driven by kickbacks to the caretakers. The result? A staggering loss of over $1 billion in foreign exchange at a time when Pakistan’s economy is in shambles, coupled with Rs300 billion in losses for farmers, who were left struggling to sell their wheat amid a surplus and crashing prices. Meanwhile, flour millers and traders are believed to have reaped enormous profits at the expense of both the government and the agricultural sector.

The handling of this scandal—and the broader wheat procurement process—has been chaotic. While the government set up inquiry committees, they have been hesitant to fully investigate key figures in the caretaker government. The Punjab government’s response to farmers’ protests was heavy-handed, deploying force to quell dissent rather than addressing the root cause of their grievances: a procurement system that is deeply flawed.

This scandal is not an anomaly—it is symbolic of a wheat procurement system plagued by inefficiency, cronyism, and an inability to balance the needs of farmers with broader economic realities. From bloated subsidies to reckless imports, Pakistan’s wheat policy has long been a patchwork of short-term fixes that only serve to deepen the long-term problems. By 2024, the situation had deteriorated even further, with wheat imports crashing domestic prices and leaving farmers in financial ruin—exactly the kind of breakdown that has come to define the country’s toxic relationship with its agricultural sector.

So what now?

Well, the good thing is that the provincial governments will have to do something about removing the wheat procurement system because the IMF has said so. It will be politically difficult, and they might drag their feet, but they will not really have much of an option if Pakistan is to keep looking towards the IMF to survive for the foreseeable future.

What will be interesting to see is how the farmers react. For many decades they have become used to procurement and government prices. And in the future, it might be a little worrying for them to plant as much wheat as they once would. Some fear this could lead to a food security issue given how much of a caloric input wheat has on the Pakistani population. However, farmers may also end up turning towards other crops such as canola, mustard, sunflower, chickpeas, and maize. There could also be a resurgence in cotton, which has seen its fate suffer thanks to a shift towards sugarcane.

However, such a significant change will require Pakistan to rationalise its attitudes towards GMOs. Take Maize as an example, and incredibly versatile crop that can have very high yields with the right seeds. Presently, Pakistan exports around $13 million worth of maize and/or its derivative products; of these, less than $3 million products are exported to Kenya (with existing trade restriction on GM maize) by Rafhan, which is 1% of Rafhan’s total sales. Sourcing non-GM maize grain in Pakistan for exports to non-GMO countries can easily be made possible, resulting in zero impact on export trade. It is estimated that such exports will require less than 30,000 tons of maize grain as raw material; a quantity easily available from KPK Province where white corn is planted. However, a majority of

But Pakistan has a huge block when it comes to considering GM foods.

The reality is that farmers and agricultural scientists have been involved in genetically modifying the food we eat for a very long time. “For many decades, in addition to traditional crossbreeding, agricultural scientists have used radiation and chemicals to induce gene mutations in edible crops in attempts to achieve desired characteristics,” reads an article by Jane Brody published in The New York Times back in 2018.

“Although about 90% of scientists believe GMOs are safe — a view endorsed by the American Medical Association, the National Academy of Sciences, the American Association for the Advancement of Science and the World Health Organization — only slightly more than a third of consumers share this belief,” states a report from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). And that is the crux of the problem. Even though the scientific evidence is overwhelmingly in the favour of GMOs, the public perception of GMOs is unfavourable.

This is mostly coming from the same brand of pseudo-science that promotes homoeopathic remedies over actual, tested, medicine that works and peddles crystal therapy and all manners of snake-oil. Robert Goldberg, a plant molecular biologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, says that such fears have not yet been quelled despite “hundreds of millions of genetic experiments involving every type of organism on earth and people eating billions of meals without a problem.”

Meanwhile, the benefits from GMOs have been authoritative. By engineering resistance to insect damage, farmers have been able to use fewer pesticides while increasing yields, which enhances safety for farmers and the environment while lowering the cost of food and increasing its availability. Yields of corn, cotton and soybeans are said to have risen by 20% to 30% through the use of genetic engineering.

Similarly in the case of Maize, provision for GM seeds would drastically increase yields and give farmers in a post-procurement Pakistan a crop that would make for very good farm economics. This is because there is a wall to how high yield can get just by improving farming practices and mechanising, something that is already difficult in a country like Pakistan where farmers do not have easy access to credit. The government has essentially been forced into getting rid of their decades old wheat subsidy. Only time will tell if they will take the opportunity to go in a direction that is good for farmers and the country.

Source Link : https://profit.pakistantoday.com.pk/2024/10/14/the-free-market-comes-to-pakistans-wheat-crop/