Why wheat and edible oil are the real inflation worries now

Wheat and edible oil inflation in India is driven by domestic supply shortages and international factors. Wheat prices remain high due to reduced domestic stocks and low harvests, while palm oil prices surged due to Indonesia’s increased biodiesel blending. Although imports could help, tariff policies and market demand for palm oil pose challenges. (Sources: The Indian Express, USDA).

Retail food inflation eased somewhat to 9.04% year-on-year in November, from the preceding month’s 10.87%.

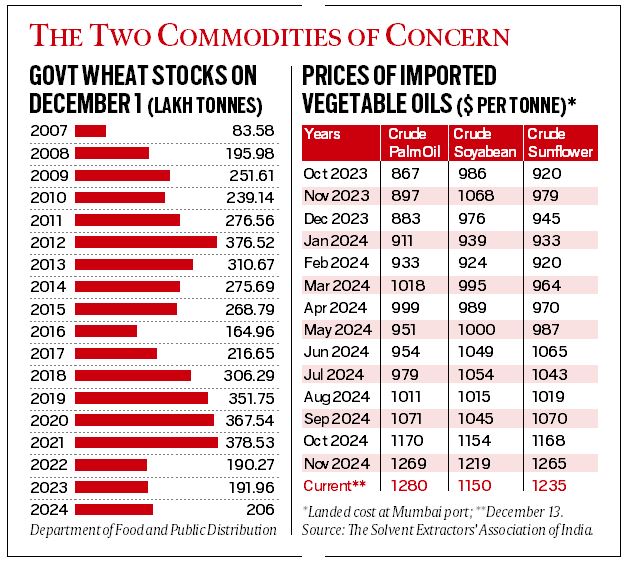

With vegetable inflation — 42.23% in October and 29.33% in November — expected to soften on the back of improved winter season supplies, two main commodities of concern remain: wheat and edible oils.

Wholesale prices of wheat in Delhi’s Najafgarh market are currently at Rs 2,900-2,950 per quintal, as against Rs 2,450-2,500 last year at this time. Annual consumer price inflation in November was 7.88% for wheat/whole atta and 7.72% for refined maida flour.

The inflation was even higher, at 13.28%, in vegetable oils. The department of consumer affairs’ data shows the all-India modal (most-quoted) retail price of packed palm oil now at Rs 143 per kg, up from Rs 95 a year ago. Prices of other oils are also higher: Soyabean (Rs 154 versus Rs 110/kg), sunflower (Rs 159 versus Rs 115) and mustard (Rs 176 versus Rs 135).

What explains the above inflation?

Wheat: Tight domestic supplies

India has had subpar wheat crops in the last three years. It is borne out by stocks in government godowns depleting to their lowest since 2007-08 (table 1) and domestic prices staying elevated despite an export ban since May 2022.

Indian farmers have sown more area under wheat this time. That, along with adequate soil moisture and reservoir water levels from surplus monsoon rains and also a likely La Niña (which should normally translate into an extended winter), has raised hopes of a bumper 2024-25 crop.

However, the wheat sown from late October wouldn’t be ready for marketing before early April. Out of the 20.6 million tonnes (mt) of public wheat stocks on December 1, about 1.5 mt is the monthly requirement for the public distribution system. Deducting that for the four months till March, besides the need to maintain a normative opening minimum stock of 7.46 mt on April 1, some 7.1 mt of wheat can be offloaded in the open market during this lean season period. In 2023-24, such open market sales from government stocks totalled 10.09 mt, which went some way in cooling wheat prices.

Advertisement

This time, not only is less wheat available for open market intervention, the prevailing prices could undermine government procurement itself. With open market rates way higher, farmers in Madhya Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana or Rajasthan may not want to sell to government agencies at the official minimum support price (MSP) of Rs 2,425 per quintal.

The import option

Thankfully, though, international wheat prices are ruling low, making imports feasible.

Russian wheat is quoting at around $230 per tonne and that from Australia at $270 from their origin ports. Adding ocean freight and insurance charges of $40-45 (from Russia) and $30 (from Australia) takes their landed cost in India to $270-300 per tonne or Rs 2,290-2,545 per quintal. That’s close to the MSP of Rs 2,425/quintal.

For flour mills in south India, imported wheat would work out less expensive than domestically sourced grain even after including port handling and bagging expenses of Rs 170-180/quintal and another Rs 160-170/quintal for transport, from say Tuticorin port to Bengaluru.

But there is a catch. Wheat imports attract 40% customs duty. Imports can happen only if allowed at zero duty. Given no elections in major wheat-producing states — only Delhi and Bihar will go to polls in 2025 — that might be politically feasible as well. Imports of 3-4 mt would help improve domestic supply and also provide a buffer against any climate-induced setbacks to the standing crop between now and April.

Edible oils: Indonesian palm factor

Palm oil is nature’s cheapest vegetable oil. At 20-25 tonnes of fresh fruit bunches and 20% extraction rate, 4-5 tonnes of crude palm oil (CPO) can be produced from every hectare.

In contrast, soyabean and rapeseed/mustard yields seldom exceed 3-3.5 tonnes and 2-2.5 tonnes per hectare respectively. Even at 20% and 40% recovery, their oil yields are just 0.6-0.7 and 0.8-1 tonnes per hectare.

Not surprisingly, palm oil is the world’s most produced vegetable oil, at 76.26 mt in 2023-24, ahead of soyabean (62.74 mt), rapeseed (34.47 mt) and sunflower (22.13 mt), according to the US department of agriculture (USDA).

Higher yields mean CPO prices are ordinarily below that of soyabean or sunflower oil. It was, indeed, so till August. The last 3-4 months have seen an inversion. The landed price of imported CPO today in India, at $1,280 per tonne, is more than the $1,150 for crude soyabean and $1,235 for sunflower oil (table 2).

The trigger for the price surge has been Indonesia’s decision to enhance the blending of palm oil in diesel from 35% to 40%. The world’s top CPO producer — at 43 mt, followed by Malaysia (19.71 mt) and Thailand (3.60 mt) — plans to roll out so-called B40 biodiesel in the coming year.

The USDA projects Indonesia’s biodiesel blending mandate — from 2.5% in 2008 to 20% in 2018, 30% in 2020, 35% in 2023 and 40% in 2025 — to result in 14.7 mt of its CPO production being diverted for domestic industrial use in 2024-25. That would, in turn, reduce the country’s exportable surplus.

How much can other oils compensate?

Out of India’s 25-26 mt annual edible oil consumption, the share of palm (mostly imported) is 9-9.5 mt.

Advertisement

Lower palm oil availability can partially be offset by higher imports of soyabean (mainly from Argentina and Brazil) and sunflower (from Russia, Ukraine and Romania) oil. In fact, palm oil imports fell from 0.87 mt in November 2023 to 0.84 mt in November 2024, while rising for soyabean (0.15 mt to 0.41 mt) and sunflower (0.13 mt to 0.34 mt). Also, global soyabean production is forecast to touch all-time-highs in 2024-25, with Brazil and the US harvesting record crops.

But there are limits to how much palm oil can be substituted. “It isn’t a consumer-facing oil like soyabean, sunflower or mustard. However, it is the preferred oil in quick-serve restaurants, sweet shops, bakeries and industries from snack-foods and biscuits to noodles,” said Siraj Chaudhry, industry expert and former chairman of agribusiness multinational Cargill India.

Being semi-solid at room temperature, resistant to oxidation and having a neutral flavour, palm oil is ideal for deep frying (required by halwais or samosa and pakoda makers) and imparting flaky texture, plus extending the shelf life, in most baked foods.

Want to go beyond the news and understand the headlines? Subscribe to Explained by The Indian Express

Crude palm, soyabean and sunflower oil imports are at present subjected to an effective 27.5% duty. Whether the government makes an exception for CPO remains to be seen.

To read more about Wheat News continue reading Agriinsite.com

Source : Indian Express